|

This entry is twice the length of my usual ones.

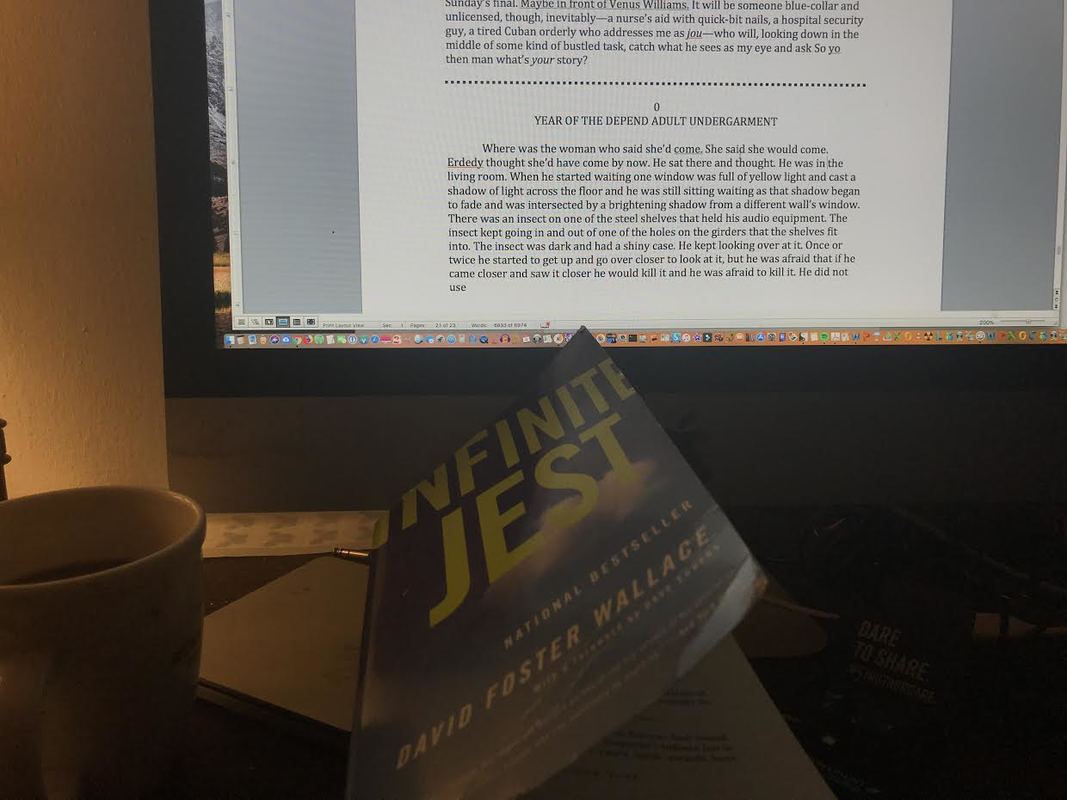

Be kind. I’m writing about a book. A big book. A really big book. I’ve started this project. I don’t know, at the moment, if I will keep it up, but so far, I’ve having great fun with it. Okay, it goes like this: Let’s start with Donald Ray Pollock. Pollock is a writer who grew up in the dirt poor Ohio town of Knockemstiff (really, that’s its name), and worked in a paper mill for thirty years. Near the end of his time there, the paper mill offered a deal in which they would pay for three-fourths of an employee’s tuition at a local college. Pollock took advantage of it, got his English degree in his late thirties and then, at the age of 45, started writing. His collection of stories, titled after the town in which he grew up, received wild acclaim. He has since written other works, and I plan to read them. My friend Tom, who turned me on to Donald Ray Pollock, sent me a link to an article in which Pollock offered suggestions for writers. In addition to the usual “write a lot and read a lot” admonition, he also gave an usual suggestion: type out a great work of fiction, word for word. Pollock mentioned typing out some 75 short stories, and in this fashion, he said, got to intimately know the style of great writers. This inspired me to do something over the past three days that has been a truly life changing experience: I’ve been typing out David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest, word for word. I would dearly love to see this through to its end. I’ve made several attempts to read the book, and never been able to get much farther than about page 150. To be sure, it’a an intimidating piece of work. Widely regarded as one of the best works to come out of the 20th Century (the book came out in 1996), the book is close to 1100 pages long, and is notorious for having close to 400 cited endnotes, all of which take up 96 pages at the end of the book. This makes reading the already intimidating work (the vocabulary alone sends me to The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary at least once a page, often far more) that much more daunting. Reading becomes a back and forth flipping exercise, in which it is easy, when in the middle of a long endnote (some of them are several pages long, and the already tiny font of the book becomes microscopic in the endnote section), to become completely lost. The endnote often goes into a digression, and it is easy to forget just what, exactly, the endnote was digressing from. And then there is the book itself, dense as compressed diamonds, which concerns itself with the nature of entertainment, addiction, sports (tennis in particular), mental illness, French Canadian separatism, sibling relations, technology, the corporatization of America, and a ton of other things that I haven’t even confronted yet. It takes, usually, half an hour to type a single page. This works out to a total of 550 hours to type the book. That, however, is a conservative estimate. The endnotes, I know, will probably take twice that long, so it is therefore probably more accurate to say that if I should get to the end of this project, I will have spent over 600 hours of my life with this book. To put this in perspective: at one hour a day, that’s almost two years. And I know there will be some days I only type one page, and some days that I don’t get a chance to do anything at all. So it may be closer to three. This doesn’t include the time, if I should keep this up, that I will spend reading the assorted study guides, which function as a kind of skeleton key to understanding the book (in a brief guide, available by clicking here, Matt Bucher, maintainer of the Wallace listserv, suggests guides by Stephen Burn and Craig Carlisle). Then there’s D.T. Max’s biography, which I’d like to read to better understand just what kind of mind thought up this book. I also sent an email to The International David Foster Wallace Society, asking them to take pity on me and give me some help--any help--to appreciate this book. And, of course, I will probably once again check out the film The End of the Tour, which chronicles Rolling Stone writer David Lipsky (Jesse Eisenberg), who followed Wallace (Jason Segel) on his book tour, when the novel was becoming a phenomenon. So far, and I really do mean this at the risk of sounding seriously pretentious—not to mention mentally unhinged—it is has been an incredibly rewarding experience. David Eggers, in his preface, said that the usual technique of trying to take a piece of writing apart as if it were a car, examining the parts and how they fit together, just doesn’t work here (it’a an alien spaceship, he says). To do so is to remove any of those parts from the other, and each word, each sentence, tends to, for want of a better way to put it, set up a kind of vibration that causes the rest of the sentence and paragraph to work in sync with those words, and causes the words to do the same with the sentence into which Wallace placed them. Therefore, I can mention a particular phrase, a particular instant, but by taking it out of the place from which I got it, I rob it of a sizable percentage of its power. There is, for example, the depiction of an hysterical mother, whose child has eaten a piece of rotten, festering mold, betraying her scientific background by running in panic within a garden she has marked off with string and popsicle sticks. “Native American straight,” Wallace’s character describes her strides, which cut perfect square corners as she runs around and around. It’a such a great choice of words, but I do it little justice by simply taking it out of the work. It is part of the mental goings on of one Hal Incandenza, tennis prodigy and top-tier genius, who is describing the workings of his mind as he suffers a breakdown while interviewing for admission to The University of Arizona. Again, Hal is a genius. He proves he is a genius with the things he tells us he says before the admissions board. Except he isn’t saying any of those things. Something—drugs? a seizure? A stroke?—has robbed him of speech, and the best he can do is flail around before the admissions board, speaking in tongues, making sounds that one member of the Admissions board describes as “barely mammalian.” That does not even begin to describe the breadth and depth of the first fifteen pages. I am sure that there will be other choices of words I encounter—I encounter of many of them, line by line, page by page—and understand why some who read this book were moved to simply say “Holy,” followed by an expletive that I will not type. A long while back, a friend of mine suggested I read this book, because this person said that, at times, my thought process reminded them of Wallace. I cannot quite believe that someone said such a thing. I mean, jeez, what a complement, whether or not it's even remotely true. And I’m still wondering if this is a blessing, or a curse. I try to imagine what it is like to have a mind that has all of the ideas and images in this book—in those first fifteen pages!—all at the same time. And there are still 1,064 to go. Right now, there are days in which I just type one page, and feel tired. I feel drained. Yet I feel something that I can only compare to my youth when, before arthritic knees made such things unwise, I ran five miles a day, and competed in several half marathons. I feel wrung out, yet I feel…invigorated, somehow, as if I’ve worked out muscles I haven’t worked out in years. I don’t know if I will finish this, but there is something wonderful about the prospect of completing this task. If I continue, I will no doubt be writing about this journey many, many more times. Stay tuned.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

|